Orange wines (sometimes described as amber wines) are white wines made with extended contact between the grape juice and skins during fermentation, a technique more commonly associated with red winemaking. This skin contact gives the wines their distinctive colour, texture and tannic structure, as well as complex savoury and oxidative flavours.

In this article, WSET educator and writer David Way explores the historic heartland of orange and amber wines on the border of Italy and Slovenia, tracing how one small, divided region helped shape one of the most influential skin-contact white wine styles of the modern era.

Orange wines are now frequently featured on better restaurant wine lists and in specialist wine shops. While not exactly common, they have established themselves as a distinct category, alongside white, rosé and red, still and sparkling. Two regions have inspired these wines: the historic wines of Khaketi, Georgia, and the tiny subregion of Oslavia/Brda on the border between Italy and Slovenia. The latter, near the town of Gorizia, has been perhaps more influential due to its accessibility: it is only two hours’ travel from Venice. What is the story of this region? What developments in the world of wine has it inspired?

Brda on the Italian–Slovenian border, Credit: Tomas Peršolja

A complex history

Formerly part of the Habsburg Empire, the region, including part of today’s Slovenia, was annexed by Italy at the end of the First World War. However, at the end of the Second World War, the hills near Gorizia were divided between what became the region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia in Italy and the new country of Yugoslavia. When Yugoslavia dissolved, the area across the border from Italy became part of Slovenia, which gained independence in 1991. Today, since joining the European Union in 2004, the border between Italy and Slovenia has little impact on daily life. If you visit the wineries specialising in orange wine, you will be surprised at how close they are (many are just 15 minutes by car from Gorizia) and how many producers have vineyards in both countries.

Today, the small orange wine region in the hills close to Gorizia is one wine region divided by a national boundary. The wineries, in the main, are grouped very close together in the hills on the boundary of Italy and Slovenia.

With less oxygen per drop and greater thermal stability, magnums age more slowly.

Gorizia, Italy. Credit: Quy Truong

Friuli and the origins of modern white winemaking

It is perhaps surprising that it was Friuli that became a centre for skin-contact white wines. More generally, Friuli is celebrated for being the region that became the first in Italy to produce modern white wines. During the second half of the 1960s, Mario Schiopetto, in the village of Capriva del Friuli, northeast Italy, was inspired by modern techniques from Germany and Austria to produce white wine in a modern style, i.e., without excessive oxidative character. The key technologies were temperature control, selected yeast, the pneumatic press, and stainless steel tanks. The wines were pale in colour, fruity in expression, without tannins and not oxidised. Consequently, Friuli became Italy's pioneer in this modern style with varieties such as Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, or Friulano.

Joskǒ Gravner and the return to skin-contact winemaking

Despite this success, less than 15 kilometres away in the village of Oslavia, Joskǒ Gravner rejected this modern style, despite receiving critical acclaim for his modern style wines. A visit to California led him to conclude that wine was becoming industrialised, thanks to the availability of modern technology.

Gravner took the opportunity of a disastrous, hail-affected harvest in 1996 to experiment with the surviving Ribolla Gialla grapes. The wine was made by extended maceration on the skins (as though a red wine was being made) and using ambient yeast. A negative review by the prestigious Italian journal Gambero Rosso followed. It praised Gravner for the wines he had made in the preceding 20 years but criticised him for his constant experimentation to try to make the perfect wine. More bluntly, it stated that the tasters did not like the wine. This did not deter Gravner, who took himself off to Georgia to learn about making wine in buried qvevri (amphorae) and made his first wine in this way in 2001. Making wines with extended skin contact from white grape varieties, Gravner was joined by other locals, including Stanko Radikon and Dario Prinčič in Oslavia (in Friuli) and Aleks Klinec (Medana), Edi Simčič (Vipolže) and Aleš Kristančič (Movia) in Brda, Slovenia.

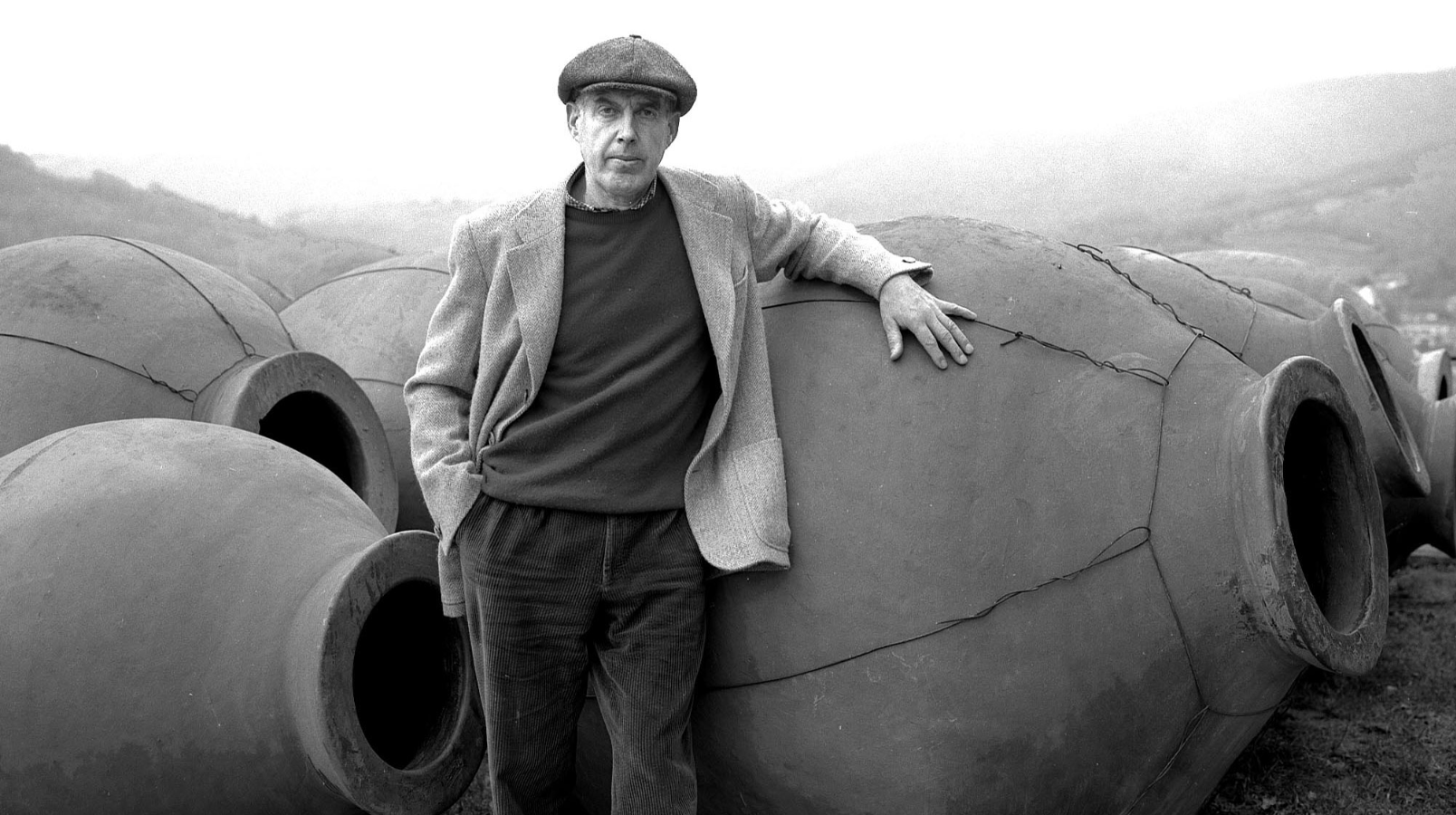

Joskǒ Gravner with his amphorae at the winery in Oslavia, Credit: Gravner

Joskǒ Gravner with his amphorae at the winery in Oslavia, Credit: Gravner

From orange to amber: Gravner’s winemaking approach

Over the years, Gravner’s style has evolved in small ways. Today, his wines are more accurately described as ‘amber’ in colour, rather than ‘orange’. This is because the extensive ageing clearly gives the finished wine a brown tint.

The key steps in Gravner’s approach are:

- Growing the local variety Ribolla Gialla, now 90 per cent of his vineyards, half in Italy, half in Slovenia

- Opt for severe crop reduction and late season picking to ensure full ripeness with botrytis, adding extra complexity to the final wine

- Including some stems if they are ripe

- The grapes are crushed and the amphorae are three-quarters filled

- The amphorae range in size from 1,300 to 2,600 litres

- Fermentation in wax-lined amphorae, buried underground as a primitive method of maintaining a cool fermentation process. Fermentation takes one to one-and-a-half months to complete

- Ambient yeast and full malolactic conversion

- Six months on the skins in the amphorae with frequent punch downs (5–6 times a day) to manage the cap and ensure sufficient oxygen for fermentation

- After six months, the wine is racked off the skins and pressed in a basket press. The wine is then transferred back to the amphorae for a further six months

- The wine is matured in very large, old Slavonian oak casks for six years and is racked every two years

- Small amounts of sulfur dioxide are added to the harvested grapes and again at bottling

- The finished wine is released seven years after the harvest, when the company believes they are ready to drink

- The recommendation is that the wine is drunk at a typical red wine temperature

- The wine is amber in colour and shows remarkable complexity with orange peel and walnut aromas, a full body, the intensity of the flavours being well balanced by firm but refined, medium plus tannins

Basket pressing after six months on skins, prior to further ageing in amphorae, Credit: Gravner

This account shows how unusual, you could say extreme, this approach is. One of the most touching features observed during a recent research visit to Gravner is the small collection of essential tools that are regularly used: wooden plungers for punch downs, a bucket, and a wooden ladder. There are a couple of concessions to modern equipment: a contemporary bottling line, used for just three days a year, and a peristaltic pump to move the wine as gently as possible. But overall, manual work and simple tools are preferred.

The wine is matured in very large, old Slavonian oak casks. Credit: Gravner

Orange wine styles in Friuli and Brda today

More generally, the style in Oslavia and Brda is less extreme. Maceration on the skins varies from a few days to three months, often in stainless steel, occasionally in wooden fermenters. Generally in Friuli, still renowned for its white wines, wineries that primarily produce conventional white wines may have one or two skin-contact wines in their range, typically macerated on the skins for up to a month. These wines are correctly called ‘orange’ in colour and combine fresh primary fruit with the classic orange peel and nuttiness of skin-macerated wines made with white grapes.

Simple wooden tools used for punch downs during skin-contact fermentation, Credit: David Way

Orange and amber wines around the world

Since the success of these wines, enterprising and inquisitive winemakers worldwide have created orange wines that have become a significant niche for adventurous drinkers. Typically, the time on skins is real but limited, perhaps up to a month, and a wide range of varieties have been used. The highly aromatic Gewurztraminer definitely has its followers, but there is no limit to the varieties that can be used. Ribolla Gialla in Oslavia/Brda and Rkatsiteli in Khaketi should get pride of place, but Chardonnay, Pinot Gris and any number of local varieties can be enjoyed in this style.

About the author

Since 2015, David Way has been part of the WSET team that wrote the current Level 4 Diploma in Wines textbooks, first published in 2019. Since then he has been responsible for updating them. He started his wine writing career on his own website, www.winefriend.org, focusing on regions that he has visited, particularly in Italy and France. On the back of his longterm interest in Italian wines, he has recently published The Wines of Piemonte in the Classic Wine Library. This is the first in-depth book to cover the whole of the region. While Barolo and Barbaresco are world-famous wines, Piemonte also has many other denominations and many local grape varieties that do not get the attention they deserve.