Germany is often described as one of the world’s great beer nations. But what does that really mean? Is there such a thing as a single “German beer culture”? And how should we think about styles that have evolved over centuries, long before modern definitions existed?

This article is inspired by the WSET webinar German beer in a nutshell, led by Markus Raupach, Germany’s nominated WSET Beer Educator and founder of the German Beer Academy. Drawing on decades of teaching, judging and writing about beer, Markus explored how history, place and practicality have shaped German beer — and why it’s best approached with curiosity rather than rigid rules.

You can watch the full webinar on the WSET Global YouTube channel.

German beer is often treated as familiar territory. Pilsner, Helles, wheat beer – recognisable names that appear on beer lists around the world. Yet behind these styles sits a beer culture shaped by regional identity, historical circumstance and centuries of local brewing practice.

Understanding German beer means understanding where it comes from, why styles developed the way they did, and why many of them resist neat classification even today.

Is there such a thing as “German beer culture”?

Talking about German beer styles sounds straightforward until you stop to think about the words themselves.

One of the first things often said in beer education in Germany is:

“There is no German beer culture.”

That usually lands with a pause and a few puzzled looks.

The point is not that Germany lacks brewing tradition. Quite the opposite. But Germany, as a unified country, has only existed since 1871. Before that, it was made up of many small and mid-sized states, each with brewing traditions stretching back hundreds of years. Over time, those regions developed their own beers, preferences and expectations.

That diversity still defines beer in Germany today. Travel across the country and you will find people drinking different beers and holding very different opinions about what counts as a good one.

The idea of fixed beer styles is also relatively new. Modern style definitions largely emerged with beer competitions around 30 years ago. Before that, most brewers were not working from guidelines at all.

Walk into a traditional Franconian brewery today and ask how they brew their Kellerbier. They will not consult a manual. They will simply make their beer, the way it has always been made there.

Styles are useful reference points, especially for education and judging. In the real beer world, however, the test is much simpler.

Are people drinking it? Are people paying for it? Is it working or not?

German beer today and how the market is changing

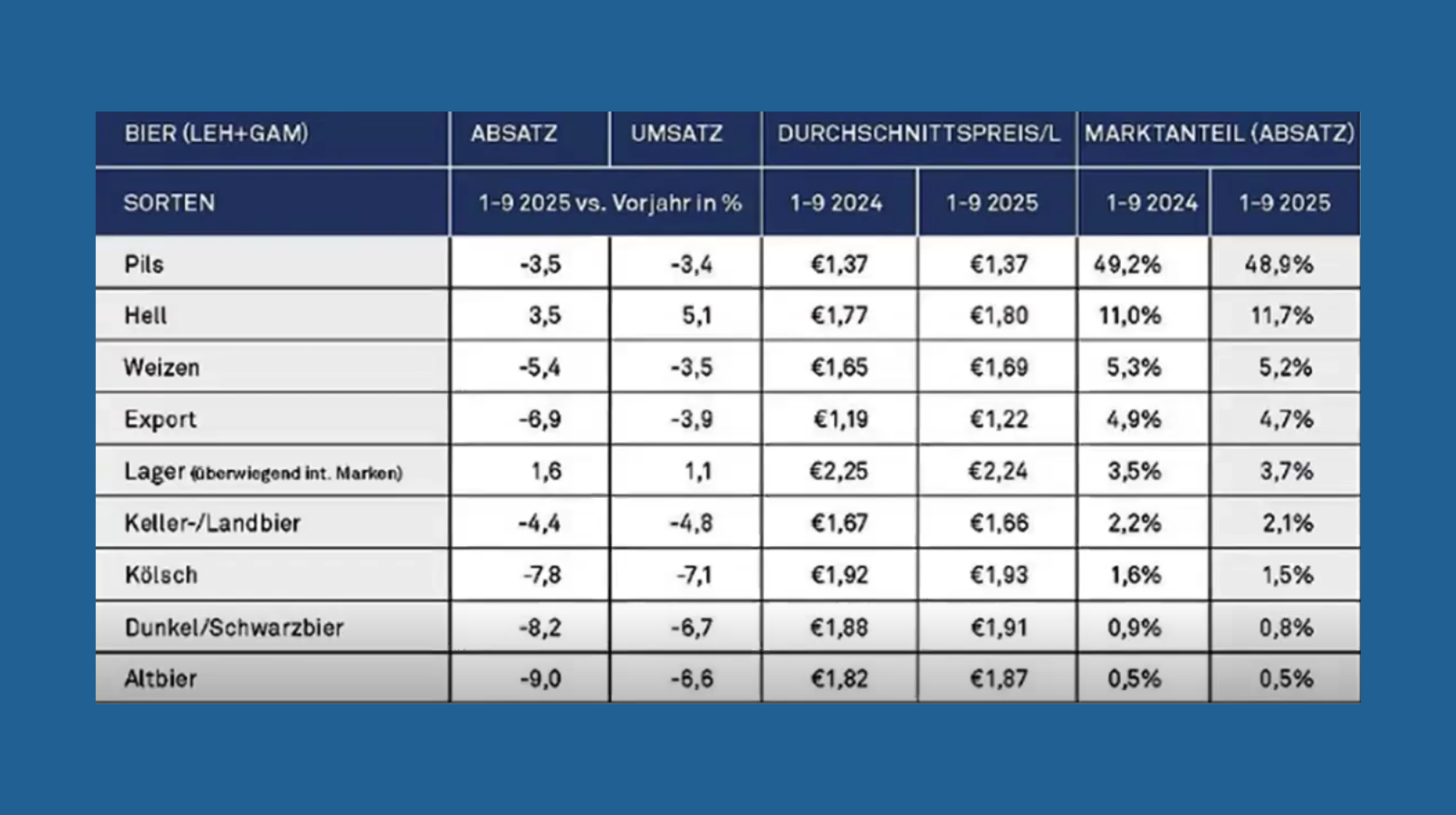

German beer culture continues to evolve, and recent figures show just how much has changed.

Per capita beer consumption in Germany now sits at around 85 litres per year, down from approximately 125 litres in 2000. This does not only mean people are drinking less. It also means competition between breweries is tighter than ever.

The number of breweries has fluctuated too. For decades, Germany had around 1,200 breweries. During the craft beer boom, that number rose to over 1,500, before falling back again following the pandemic. Today, the total sits closer to 1,400 and may continue to decline as market pressures increase.

When it comes to what Germans are drinking, Pilsner remains dominant, accounting for around half of the market. Helles has emerged as the fastest-growing style, while wheat beer, once the second most popular category, has declined.

One of the most notable developments is the rise of non-alcoholic beer, which now makes up around 10 percent of the market and continues to grow.

Most popular German beers

Traditional German ale styles and regional brewing traditions

Before clear distinctions between ales and lagers existed, most German beers were fermented under mixed conditions. Fermentation temperature, cellar environment and local microorganisms mattered far more than categories.

Many traditional German ales trace their origins back to historical brown beers. These were practical, nourishing drinks made from whatever grains were available. Over time, regional expressions developed.

Altbier and Kölsch from the Rhine region

In the Rhine region, two neighbouring cities came to represent very different ideas of beer.

Altbier, meaning “old beer”, developed in Düsseldorf. Despite the name, it is not a relic. It is a continuation of earlier brewing traditions, typically amber to brown in colour and fermented warm before cold conditioning.

Just down the river in Cologne, Kölsch emerged as a pale, top-fermented beer. The rivalry between the two cities, and their beers, remains one of Germany’s most famous and good-natured brewing debates.

Berliner Weisse and its historic roots in Berlin

Berliner Weisse is often described today as a sour beer. Historically, that description misses the point.

Traditional Berliner Weisse was lightly tart, low in alcohol and highly refreshing. It was designed to be drunk in large quantities, particularly in summer beer gardens. Strong acidity would have made that impossible.

Historically, Berliner Weisse was fermented using complex mixed cultures, including ale yeast, lactic acid bacteria and other microorganisms. The beer was not boiled, and wooden vessels provided the ideal environment for these cultures to develop.

At its peak in the early nineteenth century, Berlin had around 300 Berliner Weisse breweries. Following the rise of Bavarian lagers and the devastation of the Second World War, the style almost disappeared.

Today, only a handful of breweries attempt truly traditional versions. Many modern interpretations rely on simple kettle souring, producing sharper acidity than the original beers ever had.

An example of historical Berliner Weisse glasses

Gose beer and its regional identity

Gose follows a similar story.

Originating near the town of Goslar and later embraced by Leipzig, Gose was brewed for export along long trade routes. To help the beer survive transport, brewers used salt and coriander, ingredients readily available through Hanseatic trade networks.

The result was a beer that was subtly salty and gently spiced, not aggressively sour. As with Berliner Weisse, modern versions often exaggerate acidity, moving away from the balance that originally made Gose such a drinkable beer.

The town of Goslar

German lagers and how technology changed brewing

Lager brewing in Germany changed dramatically with the invention of artificial refrigeration.

Before ice machines, brewers relied on natural ice and seasonal brewing. Stronger beers such as Märzen were brewed in spring and stored through summer, while Kellerbier represented the everyday beer of local communities.

The ability to control fermentation temperatures year-round transformed brewing and made pale lagers possible on a much larger scale.

How Pilsner and Helles shaped pale lager in Germany

The birth of Pilsner in 1842 marked a turning point. Its impact was not only about flavour. It was about appearance. For the first time, drinkers could see their beer clearly through glassware. Its bright, golden colour set it apart from darker, cloudier beers.

When Pilsner arrived in Munich, local brewers responded with Helles, a pale lager brewed with softer water and lower hop bitterness. The style was introduced cautiously and tested outside the city before being adopted locally. Once its success was clear, it quickly became part of Munich’s brewing identity.

From there, pale lager styles spread rapidly, reshaping beer cultures far beyond Germany.

A Pilsner brewery & Helles at Oktoberfest

Kellerbier and smoked beer: living traditions

Kellerbier remains one of Germany’s most historic and least defined beer styles. Often unfiltered and unpasteurised, it reflects local ingredients, water and brewing practices. There is no single correct version, and that flexibility is central to its identity.

Smoked beer is not a style but a technique. Any beer can be brewed with smoked malt. Historically, all malt was smoked before indirect kilning methods were developed. Bamberg’s Rauchbier preserves this older flavour profile, producing beers that are intentionally smoky and deeply rooted in place.

An example of some smoked beers

Why German beer resists strict style definitions

German beer is not defined by a single tradition or a neat set of styles. It is shaped by geography, history, technology and practicality, as well as by generations of brewers making beer for their communities.

Understanding German beer means letting go of rigid definitions and paying attention to context. Styles can guide us, but they were never meant to replace lived tradition.

Or, put simply: if people are drinking it, paying for it and enjoying it, then it is doing its job.